| This article is an original piece from Enspire Science Ltd, a consulting and training service provider for research institutions and individuals, with decades of expertise in EU funding. Enspire Science Ltd provides, within other services, a free 'Go/No Go' screening service that can assist you in evaluating whether your project’s concept is in line with the requirements of the targeted grant. For more information, please visit their website here. |

Winning a Horizon 2020 grant is no easy task. Such a feat constitutes an impeccable project proposal which presents the project in the best possible way to its reviewers. As an applicant, having a deep understanding of the Horizon 2020 proposal template and structure will undoubtedly help to write such an outstanding proposal. Therefore, a logical first step to developing the Horizon 2020 project proposal is to first and foremost review and understand the template’s requirements. Attempting to do so often results with one main issue. Time and again, we bore witness to the tremendous “logic gap” which exists between what researchers assume the proposal template requires of them and what we know reviewers are most definitely looking for. Therefore, our team has put together years of shared experience into one complete guide. This will help you navigate the proposal template space using our offered inner logic.

Horizon 2020 Proposal Templates

All Horizon 2020 project proposals are required to be presented in a specific outline. This is dictated by the Horizon 2020 proposal templates. There are unified templates dedicated to RIA/IA projects proposals, CSAs project proposals, MSCA project proposals, ERC project proposals, etc.

Off the bat, the idea behind the templates is in fact positive. It provides applicants with a clear and uniform structure to all competing projects. Still, there are some discrepancies associated with these templates and the inner logic does not always make sense intuitively. While this article focuses on the inner logic of the most “popular” template for the Horizon 2020 RIA/IA project proposals, most of the insights can be easily adapted to all other proposal templates (except for ERC grants).

How not to tell the same story 3 times – The typical Horizon 2020 proposal template mistake

In many cases, applicants approach the Horizon 2020 grant writing process with a very premature idea for their project. Equipped only with this early-stage idea, they hit the ground running drafting an initial work plan that is then divided into work packages.

Though this seems like the most natural approach, this is usually not a good starting point for writing the Horizon 2020 project proposal. As explained in more detail below, the Horizon 2020 project proposal should first and foremost offer a clear presentation the project’s concept. Only after should it present its detailed work plan for execution. Generally, starting with the work plan means the concept itself is far from being truly articulated.

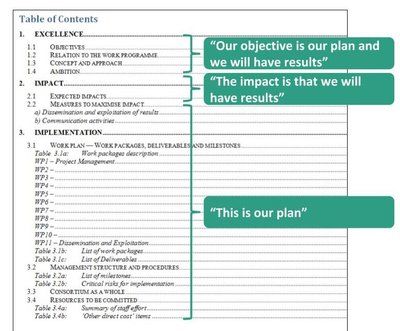

Therefore, a very typical and frequent mistake which stems from the above approach is a project presentation that revolves around its work plan. Unfortunately, the ‘other parts’ (the highly important ‘Excellence’ and ‘Impact’ sections) may end up being derived from the work plan and lack the conceptual thinking they demand. Roughly speaking, we can say that such a project proposal resembles the following “story”:

Needless to say that this is not a good “feeding the reviewer” practice. The reviewers simply won’t find the answers to what they are looking for (in both ‘Excellence’ and ‘Impact’ sections) in such a project proposal presentation.

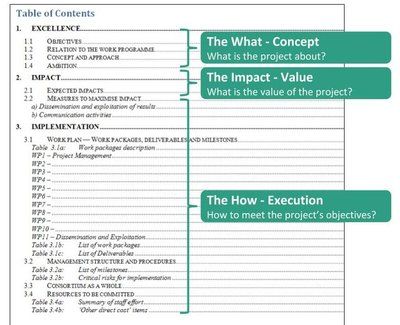

Instead, a good practice should present a project in the following manner:

This kind of presentation respects the template structure and provides the reviewers with the right information in the right place.

To achieve this foreseen logic of the template, we must first disassemble the template in its entirety and strip it of all assumptions and understandings. Moving forward, we’ll reassemble the template section by section, creating a new and holistic inner-logic approach.

The inner logic of the Horizon 2020 proposal template: “The What” and “The How”

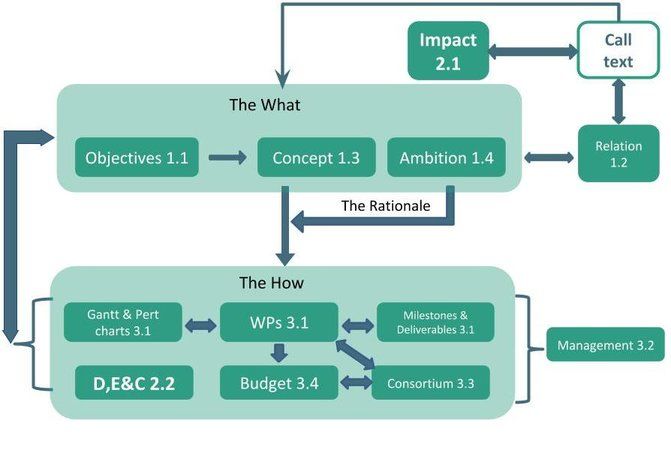

The first and highly important stop in this process is the Call text. The project proposal must be in line with all the requirements of the call text. In the competitive environment of Horizon 2020 – we strongly recommend not to neglect any piece of the call text when constructing your project proposal. Having an excellent project at hand may not be enough. If it does not refer to all the elements of the call text – the project might not be ranked high compared to other projects that do cover all the elements. As a rule of thumb, we advise to have the Call text handy throughout the proposal development process and to revisit it often. This will help in verifying that the proposal presentation does not divert from the Call text requirements as the proposal develops.

Our most high-level distinction in the Horizon 2020 proposal template makes a clear divide between what we’ve termed as “The What” and “The How” of the project. As we continue, we’ll define each high-level section, and identify which sub-sections belong to each part.

As a general starting point, meaning the Call text, should lead first to the project’s definition of “The What”, and only after that we should attend to “The How” of the project at hand.

“The What” of the Horizon 2020 proposal template

“The What” is essentially the conceptual presentation of the project proposal. In other words: What is it that you want to do and achieve with this project?

“The What” consists of the following sections in the Horizon 2020 proposal template: Objectives (section 1.1), Concept and Approach (section 1.3) and Ambition (section 1.4). Let’s examine the requirements of each section, as well as their inter-relations.

Section 1.1 – Having a clear distinction between “The What” and “The How”, the project objectives in section 1.1 should be conceptual rather than operational or technical (don’t worry, we’ll get to these later on in section 3.1). Typically we recommend allocating no more than 2-3 pages for this section.

This leads to a typical issue around the correct spot for the inclusion of the background information of the project. Section 1.1 does not need to include background information, most certainly not the opening text. Surprising as it may sound – the background information is expected as part of the Ambition section (section 1.4) next to the description of the State of the Art and the need for the project.

The role of the Ambition section (section 1.4) is to provide the rationale for the project. Indeed its position (being the 4th section in the “Excellence” section) does not make much sense, but this is where it was located and this is where the reviewers expect to read this kind of information. Keep in mind the following: one of the things reviewers don’t like is reading lengthy background texts before getting a clear understanding about the project concept and main idea. Therefore, don’t place the background in section 1.1 and instead get to the point as soon as possible.

Section 1.3 – The concept and approach in section 1.3 should give a conceptual presentation of what the project is about. This is one of the most important sections in the proposal. It links the project objectives to the full project presentation, and serves as the portal to “The How”: it is perfectly fine to make an initial reference to the work plan in section 1.3, but keep the fine details of “The How” for later. Use section 1.3 to explain scientific and technological methods that you may employ in the project. This is also a good place to stress out the innovative aspects of the project, but without overlapping with section 1.4. A well written section 1.3 can make a difference in the eyes of the reviewers and serve as a defining factor during their decision making.

Section 1.4 – As already mentioned above, this section essentially provides the rationale of the project. It refers to the need, the state of the art, and how this project will progress beyond the state of the art. Section 1.4 is the place to clearly explain the innovative nature of the project. The state of the art should provide all the required references to prior work or existing findings. It is imperative to be very clear about the progress this project will have compared to the state of the art without repeating text from previous sections. Some may recommend putting this kind of comparison in the form of a table, to make it easier for the reviewer to read. As a personal preference, we believe that clear, logical texts prevail over anything else.

“The How” of the Horizon 2020 proposal template

“The How” essentially gives very practical information about the actual project structure and its execution. Its role is telling the reviewers what the project will contain: tasks, milestones, deliverables, budget, etc.

It is imperative to have a well-thought execution plan in the proposal. This is done for two complementary reasons: 1. to make sense in the eyes of the reviewers and help them realize how the requested budget was constructed. 2. to make it easy to actually execute the project, once retained for funding. Experience shows many applicants that were all too focused on creating a competitive project plan in order to stand out in the eyes of the reviewers. The result was a substantial neglect to how they will actually execute the project once funded. To no surprise, they had complex difficulties with the execution plan once they began work. Make sure the plan both makes sense to the reviewers and yourself.

“The How” includes various sections in the proposal templates. Not all of them carry the same weight or importance, but all must be attended to. The full list includes the entirety of section 3 in addition to section 2.2, found under the “Impact” section.

Section 3.1 – We’d recommend opening section 3.1 with a work plan overview which formulates the following two points:

Links the objectives (section 1.1) and concept (section 1.3) to the work packages (WPs) structure – explain how the WPs structure stems from the objectives and concept;

Explains how the WPs will actually lead to reaching the project objectives – loopback to the project goals and objectives.

This text should be about one page long. If possible, we’d recommend adding graphical representations of these links.

The work packages (WPs) are the main place for conveying practical information about the project execution. For each WP we are required to list operational objectives, followed by the content of work (tasks or any other form of description) and then a set of deliverables.

Tips for WPs:

- In the past, in some instances, the EC had limited each WP text to no more than two pages. This rule is no longer applied, but we still recommend adhering to it. The two pages rule will assist you in presenting clearer messages and an efficient WPs structure.

- The WPs is not the place to present conceptual objectives or aspects of the project. For that there exists sections 1.1 and 1.3.

- The best way to present the work plan is by listing concise tasks that refer to the methods described in section 1.3 (without repeating them).

- Deliverables should be listed per WP. We’d recommend having no more than 2-3 deliverables per WP. It is quite common to present more deliverables than that, but what you have to know (or remember), is that unlike many other elements in the proposal text, the deliverables will turn to be contractual obligations once the grant is selected for funding and the agreement is signed. This means that if you list more deliverables in the proposal development phase, you will be obliged to produce more deliverables in the execution phase as well.

- The above point also goes for the Milestones (in section 3.2), as they turn to be contractual obligations once the grant agreement is signed. Typically 3-5 milestones in a 3-year project should be enough. No need for more than that.

- Add a Gantt and Pert charts as required, which corresponds to the suggested WPs structure. We recommend using a dedicated software for that (not Excel). Make sure the charts are understandable to the reviewer (many times they are not due to overload of fine details in small fonts).

Section 3.3 – Consortium as a whole. In this section the reviewers are expecting to learn about the synergetic nature of the project and why the consortium partners were selected to participate. A typical mistake is to replicate in section 3.3 texts from partners profiles in section 4.1. Instead, make sure to focus on the functions that the consortium partners fulfill and how these functions contribute to reaching the project’s objectives. It is important to ensure there are no gaps in functionality but also that there are little to no overlaps between the partners in functionality. From experience, many choose to mention the consortium’s geographical distribution as an explanation. While it can be mentioned, it only holds real value in that case that it is linked to the functionality of the partners.

Section 3.4 – Officially: “Resources to be committed”, or simply put: “the budget”. This section quantifies the actions mentioned earlier in the text into a monetary representation. The tasks are translated into person-months allocations and other budget requirements. Section 3.4 is the place where the reviewers should assess whether the “price tag” of the project is accurate and that the costs are justified. Make sure to link well the content of section 3.4 to the actual execution plan described mainly in section 3.1 as it will strengthen the overall case for the requested budget.

Section 3.2 – This section presents the project’s management structure, which will be responsible for orchestrating all the pieces presented in section 3 (+ section 2.2). It should include lists of project executives and their roles, such as project coordinator, scientific leader, admin & financial manager, exploitation manager, etc.; committees such as ethics, IPR, etc.; and boards advisory, exploitation, etc (as needed). It should also list the project’s bodies, such as the general assembly, task forces, steering committee and/or executive board (as needed). Finally, this section should also include a list of management procedures, such as decision making, production of deliverables and reports, project meetings, communication flow, conflict resolution, etc. Section 3.2 should be represented in the work plan as one of the Work packages (typically as WP1).

Section 2.2 – Although it officially ‘belongs’ to the “Impact” section, its nature is in fact an operational one, hence it is listed here under “The How”. In this section we are requested to present the Dissemination, Exploitation and Communication plans, which in turn should be referred to from the respective Work package under section 3.1.

What’s left?

Section 2.1 – We’ve covered “The What” and “The How” so far. The main missing part is the Impact, which is presented in section 2.1. This section is highly important in Horizon 2020 and should be regarded as such.

When writing the impact section (section 2.1) keep in mind the following:

- The impact text should be very different than any other text in the proposal, as it has different goals and points of focus.

- It is a typical mistake to confuse impact with outputs of the project, when the two are greatly different. Make sure you create a unique case for each.

- The impact of the project represents the value of the project.

- The impact must correspond to the expected impact listed in the call text, but also to the Horizon 2020 key performance indicators and cross cutting issues.

- There are various dimensions to impact: scientific, academic, socio-economic, environmental, public and commercial. Attend to all that are relevant to the project.

Section 1.2 – Relation to the call text. We left this one to the end to close the loop. Since we started with the call text, leading the proposal development process, and in line with our recommendation to keep the call text next to you in the process and revisit it often, we believe that this section should be addressed last in the writing process. This is the point in time when you have a much better overview of the project, compared to the beginning of the process. The role of this section is not to tell the project’s story again, as many do. The role of this section is to hand out a clear and concise summary to the reviewer, reflecting why this project proposal addresses the call text requirements. When doing so, use the call text lingo, but don’t be too direct in referring to the call text. A good section 1.2 should not be more than 1 page long.

Having defined all sections of the Horizon 2020 proposal template, it is clear why a comprehensive understanding must be the first step in the proposal writing process. As you continue to write, make sure to adhere to the Horizon 2020 proposal development timeline.

You may contact your H2020 NCP, or directly Enspire Science Ltd for any additional assistance.